"WHAT are you listening to?" Since my dad usually didn't address me except to criticize my posture, I looked up. The year was 1968, and I was lying on the living-room carpet with my head between two cheap stereo speakers. "Blues," I replied. I didn't add that the LP was made by Peter Green's Fleetwood Mac; it would have required too much explanation.

Dad grunted. A former naval officer who had traveled the world, he associated his fellow servicemen's blues records with licentious behavior, maybe including his own. His grunt even betrayed a hint of acknowledgment that his 17-year-old spawn was finally growing pubes.

Of course, Dad figured that my record was made by African-Americans. Never having heard Mike Bloomfield or John Mayall, and only vaguely aware of Bob Dylan or the Rolling Stones, he assumed that white boys did not play the blues. And he could have been forgiven the assumption, because Fleetwood Mac were accurate imitators.

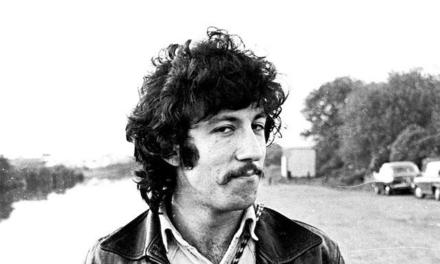

Peter Green played bell-ringing electric guitar directly derived from B.B. King and Hubert Sumlin. Bandmate Jeremy Spencer's tunes, vocals and slide guitar were snatched wholesale from Elmore James. Early Fleetwood Mac possessed only two claims to originality: drummer Mick Fleetwood's distinctive way of rolling the tomtoms, and the sensitive white soul of Green's voice.

Fleetwood Mac courted credibility by recording a 1969 double album in Chicago with Otis Spann, Willie Dixon, Buddy Guy and other black blues progenitors. Today that would be called appropriation, examples of which abounded at the time. Led Zeppelin grafted uncredited cops from Albert King, Howlin' Wolf and Dixon into "How Many More Times" and "Whole Lotta Love." Savoy Brown, Chicken Shack, Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation and other white Brit groups based their repertoires on American blues songs and inserted snatches of favorite lyrics into their own originals. From Elvis to the Rolling Stones to Deep Purple to Grand Funk to, heck, David Bowie, Hall & Oates, Boz Scaggs and Eminem, white musicians have been mining black forms since the advent of Dixieland jazz.

But there was no denying either the genuine passion Keith Richards and Eric Clapton held for their models or the creative transformations erupting in songs such as the Stones' "Midnight Rambler" and Cream's "Strange Brew." The best white artists made art from the bones of their influences, as everyone does, and Fleetwood Mac quickly fled its safe status as a purist blues band.

Peter Green & co. made a jarring border jump in 1968 with two black-to-white English hits -- first the blues rumbler "Black Magic Woman," then "Albatross," a dreamy instrumental with zero Chicago connotations. Their biggest international success began in 1969 with "Oh Well," a brilliant piece of schizophrenia that progressed from a hyperkinetic blues riff to a slow, grand instrumental with a damned wooden flute in it. Fleetwood Mac's ironically titled 1969 U.K. Top 10 album "Then Play On" -- offering a variegated mix of new guitarist-singer Danny Kirwan's gentle sway ("Coming Your Way"), the group's crazed jams ("Fighting for Madge") and Green's primal blues ("Rattlesnake Shake") -- became Green's last full-length with the band.

The pressures of fame, the band's artistic fragmentation and liberal doses of LSD had broken Green. He signaled his distress in early 1970 with a monumental last single, "The Green Manalishi," whose crushing riffs, terrifying mood and scathing lyrics about the satanic power of money leave no question about Green's motivation for his withdrawal from Mac and from the world; he made only sporadic appearances for the rest of his life.

What a loss. His confiding voice drew us in; his leaping guitar solos cut to the heart of pain; he led one of his era's most exciting bands (a wonderful example being the 1970 concerts preserved in Fleetwood Mac's "Live in Boston"). Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie, obviously, played on to enormous success with talented new collaborators. But never with the daring spirit that possessed the band's founder.