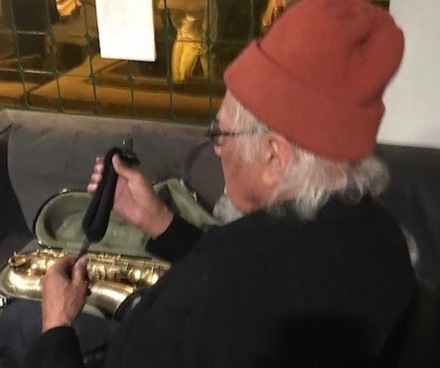

Charles Lloyd cocked his ear toward the din of heedless revelry and bent way down so he could speak into his sax microphone. "If you don't want to hear no music," he intoned like a priest in a confessional, "get the f*ck out of here."

The young men with facial scruff and the young women in clubbin' finery might not have especially wanted to hear an old guy, even a famous old guy, play jazz. But responding to the note of authority, they shut the f*ck up.

The occasion was the debut of a wristwatch, the Blue Note G-Shock, displayed in vitrine at the back of this small Silver Lake dance bar. Casio, Don Was and Blue Note (Lloyd's label) had partnered to create a timepiece that would pair, the ad copy explained, America's greatest art form with legendary Japanese refinement. The watch looked more like an accessory to fisticuffs, but it had some blue on it. Maybe it will inspire somebody to Google "saxophone."

Lloyd had come to demonstrate American art, so he did, with the help of an unusual band. Most surprising, behind celebrity sunglasses, was Jim Keltner, best known for knocking out solid rock drums with the likes of Eric Clapton and Bob Dylan. He also digs jazz, though, and Lloyd has known him since the Beach Boys were actual boys. Less surprising but new to the Lloyd stable was the guitarist son of the late big-band leader Gerald Wilson, Anthony Wilson, who has teamed with Keltner quite a bit. Craggy Greg Leisz has been stroking the pedal steel with Lloyd since the saxist has steered his recordings in a more country-folk direction the last few years. And plucking electric bass was sarcastic young Mai Leisz, whom Greg did not marry solely because she's from Estonia, site of a landmark 1967 Lloyd live recording.

Afterward, Lloyd complimented Mai: "You held us together!" "I just played," she shrugged. "What key were we in? Who knows." Her sturdy simplicity did prove useful, with Keltner in abstract mode, Wilson emphasizing the melodies and Greg Leisz playing his usual role as color man and brilliant cornpone astronaut.

In a weird, loose way, the set rocked. A Lloyd friend said it reminded him of psychedelic days at the Fillmore, and when asked about a vibe of Quicksilvery Bo Diddleyism and Grateful Dead jauntiness, Lloyd was quick to express his admiration for John Cipollina and Jerry Garcia, both of whom he knew. "John was a great collector of rare records," he remembered. "And Jerry, he knew every kind of music." Lloyd also responded to comparisons to his '50s days backing Howlin' Wolf in knifegut Southern saloons: "I was a teenager! There'd be fights on the dancefloors and dice games in the back. And the women -- psssshhhh! They loved the way big Wolf howled 'Ah-oo-oo!' I still feel him the most."

Lloyd summoned more edge than usual on tenor and flute, communicating the joyfulness of Ornette Coleman's "Ramblin'" and his own similarly rambunctious 1965 "Of Course, Of Course." (Although usually tagged for his John Coltrane influences, Lloyd arrived in Los Angeles from Memphis in 1956, just as Coleman was breaking out here, and the change of the century did not escape him.) You can't be a modern American without somber moments, though: "Defiant" found pale hope in beauty, while the concluding ballad "La Llorona" wrung our hearts nearly to despair.

Your reporter had the privilege of carrying Lloyd's tenor to his car in its black form-fit case, and placing it just so in the back seat with the handle easily accessible. No tip was necessary.

* * *

PHOTOS BY FUZZY BLUE.