This was a remarkably intimate and satisfying foray even for Charles Lloyd, and his standards are way up there.

80-year-old sax great Lloyd and 34-year-old piano prodigy Gerald Clayton began their duet with Billy Strayhorn's "Blood Count." One of the Duke Ellington arranger's last compositions, it's a sigh of wistfulness, pain, almost despair. And like everything Strayhorn created, it's beautiful. You couldn't ask for two more suitable interpreters -- Lloyd's transparent tenor breathing the emotion; Clayton's ethereal keys portraying the gathered friends, the bedside flowers, the light through the window. This level of delicacy and understanding can't fail to make listeners vibrate like a tuning fork. Was it okay for us to start with a tear? Yes.

Naturally attuned to suffering, Lloyd found himself in an especially sympathetic state amid the recent California conflagrations, since fire temporarily drove him from his Montecito home a year ago. A desire to affirm life and roots could account in part for titles such as "Defiant," a swing ballad highlighted by Clayton's bluesy rumble and Lloyd's soul testimony; and "Booker's Garden," a jumping flute celebration of trumpeter Booker Little, Lloyd's boyhood friend who died young in 1961 -- Booker's memory would bring joy, if Clayton's striding left hand and Lloyd's vigorous rattle-shaking had anything to say about it. And though the European melodiousness of "Blow Wind" emerged quietly, Clayton built up enough dissonance and Vladimir Horowitz-style passion to extinguish any flaming menace like a birthday candle.

The overall mood, though, was deep and pensive, especially on "Rabo de Nube" and "La Llorona," the kind of Spanish-flavored plaints that can wring hearts best through the bell of Lloyd's tone-shaping tenor. We have loved Lloyd, though, for half a century, so the greater revelation was Clayton. Son of bassist-bandleader John Clayton and named after another monumental bandleader, Gerald Wilson, the pianist showed that he considers the heritage no burden. He shifted subconsciously among classical, jazz, samba, blues, folk and avant-garde expressions as if he had combined them all into his own native language. His touch was sure but sensitive, his harmonic sense unbounded -- the way he layered sustains at the end of a song was worth the ticket by itself. And oh, did he LISTEN. His few years with Lloyd have borne copious fruit.

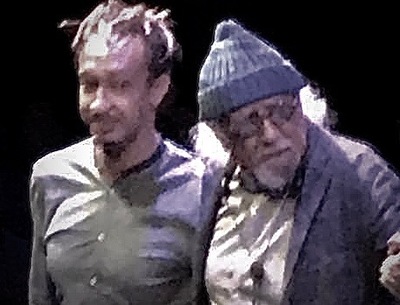

Listening takes two, and Lloyd always does that, now more than ever as the days grow shorter. But if Lloyd, relaxed in loose jacket and elvin cap, heard his train a-coming, he made the distant whistle just an instrument in his orchestra.

* * *

PHOTO BY FUZZY BARK.