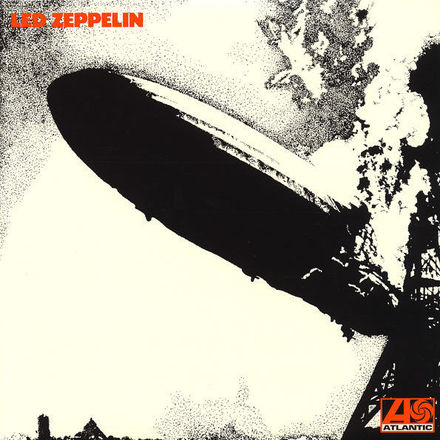

Yesterday the driver with the shaved head and the chin tuft was slapping the door of his pickup truck so hard that I could hear it over the music he was emphasizing, and that meant HARD, because the song was busting eardrums in my adjacent car with the windows up. The driver's papa must've been unborn when the album called "Led Zeppelin" lifted off in January 1969, but the 2018 trucker got the message same as his granddad.

The impact came from the way Zep guitarist Jimmy Page thought about rock music: You dangle something pretty to get a listener leaning in, then you make a fist and flatten the sucker. The truckdriver got his head snapped back by "Babe I'm Gonna Leave You," a folksong Page had first encountered via an interpretation by . . . Joan Baez! And although Zeppelin is often accused of dumb clobber, Page achieves his knockout with a fingerpicked acoustic intro, followed by acoustic flamenco strumming, followed by a doomy downward progression on John Paul Jones' electric bass and his own subtly layered guitars. No amps turned up to 11; the deathly drive arises from John Bonham's massive slog -- drums had never been recorded this full, this bottom-heavy, this LOUD. And Robert Plant -- what a range, from whisper to SHRIEK.

The world had been waiting for this sequel to Cream and Hendrix, and Page believed that enough to tape "Led Zeppelin" with his own money and no label. During a tour of Sweden, the band had tried out the material on puzzled audiences expecting the Yardbirds. Tried out, not worked out, because the whole album was founded on live jams in London's superb Olympic Studios, whose advantages Page had appreciated through his vast experience as a session musician. Tracks like "Babe," the bashing "Good Times Bad Times," the riptearing "Communication Breakdown," the exotically dynamic "Dazed and Confused" and the armored riff-trundler "How Many More Times" would have served as sufficient building blocks for an exceptional edifice, but a trickbag of studio effects gave it psychedelic currency, and the players' urgent spontaneity gave it real thrill power.

Due to a budget that discouraged fixes, "Led Zeppelin" retains a whole lotta mistakes. On "How Many," the usually faultless Jones attempts one rare bass chord and sticks a wrong note in it. Always improvising (and his musical instincts always correct), Plant sometimes doesn't bother to frame the words, as when he sings "It's my turn to cry" in the Hendrix/Traffic steal "YOUR Time Is Gonna Come," or when, leading into Page's solo on "Communication Breakdown," he yells, "Ohhhh . . . sumpin'!" Page wanders all over borders of beat and measure when soloing on "Dazed," and throws off the whole band when he mistimes a sting on the slow blues "I Can't Quit You Baby."

Such miscues got chiseled in granite not only because repairs would have cost, but because producer Page knew brilliance when he heard it and understood that imperfections actually contribute to the excitement of superior musicians racing toward a cliff blindfolded. That's one reason "Led Zeppelin" was a canny choice for the favorite album of Amy Adams' self-scarifying character in the HBO series "Sharp Edges."

Plenty of tight-asses have whined about Page's wavering precision, but nobody with a beating heart could fail to sweat along with the pure rock energy busting from his demonic digits. Crucial to his freedom was the plowhorse team of steady Jones and mighty Bonham, Bonzo exhibiting far more craft than he usually gets credit for -- listen to the way his rolls and accents push against the beat on "Good Times" and "Dazed," setting up tension for the riffs' release; his cymbal crashes are always tossing you around like surf waves, unless he's ticking out sarcastic metronome rhythms on his high hat. No one had ever heard a man wail like Robert Plant, whose androgynous, poodle-haired back-cover photo raised doubts as to whether Zep had hired some kind of Joplin imitator. Did the typesetter accidentally omit his first name's final A?

Fast followed slow, even in the same song. Track followed track instantaneously, not after the standard polite pause. And with the help of engineer Glyn Johns (who'd previously knobbed the Rolling Stones, Small Faces, Steve Miller and Procol Harum), Page conjured a sound field that made you feel you weren't just listening to the band, but dancing in the middle of it.

"Dancing Days" would come later, as would "Whole Lotta Love," "Immigrant Song," "Stairway to Heaven," "Kashmir" and the rest. But Led Zeppelin got it right the first time.