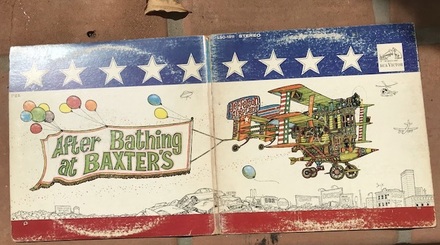

My LP cover has a hole gouged in the lower right corner. The hole stigmatizes Jefferson Airplane's "After Bathing at Baxter's," released in November 1967, as a "cut-out," meaning RCA pressed too many LPs, and they didn't sell. The mutilation served as an excuse to unload a lot of them cheap.

Backstory, early '68. I'm talking music with high-school classmate David Lee, who'll soon change the world again by lending me the first Led Zeppelin album. Dave says his dad owns a drug store that stocks records, and he can get me "Baxter's" for a buck. Having worn out the Airplane's earlier 1967 album, "Surrealistic Pillow," I say sure.

I take it home, slap it on the family's crappy little portable record player, and HAVE MY MIND BLOWN. This wild beast is no "Pillow." The very first sound that oozes from my lo-fi single speaker is a shivering wave of guitar feedback, and the experience barely gets nicer from there. Atop a chopping, scraping rhythm, a dude with a voice like a crypt keeper (rhythm guitarist Paul Kantner) drones about acid-fried alienation while Grace Slick dances vocal arabesques around him. They conclude this "Ballad of You and Me and Pooneil" (wha?) with words that stab through the corner of my skull like the knife in Hitchcock's "Psycho": "Will the moon still hang in the sky . . . when I die? Die! Die! Die! Die!"

"Baxter's" grudges only one fine almost-ballad -- Kantner's perkily pondering "Martha"; the rest rages, jams and trips with rock energy, dense and dark. I find it terrible, in both senses. But having invested a buck, I don't give up. Gradually, the songs filter into my teenage brain as unconventional but cunningly structured ensemble pieces that express the pre-Manson, pre-Altamont nosedive of hippiedom the way nothing else ever will. Overlooked by almost everyone and boasting no radio hits, "Baxter's" becomes my favorite rock album of all time, one I never put on without playing the whole thing.

Flash forward to now, as I clamp on headphones to focus a microscope on the music's virtues. The radical stereo panning by producer Al Schmitt (Lalo Schifrin, Neil Young, Jackson Browne) keeps instruments and voices jumping all over the place, reflecting the spontaneity of this explosive creation. And those voices: Alternate takes and contemporary live recordings make clear that Kantner, Slick and high-soulful Marty Balin didn't plan a damn thing, they just stepped up to the mike and went at it. Sometimes they sing in unison, sometimes in something like conventional harmony, often in terra incognita, adventuring across three-part convergences that snap with the chemistry of very different personalities. This, I wrongly projected, must be the future.

In addition to her exotically mesmerizing vocals, Slick makes definitive contributions all over the record: spooky recorder on "Martha," belly-dance harpsichord on the skull-cracking "Two Heads," dissonant piano on the moody Leopold Bloom takeoff "Rejoyce." She's a team player in the same way as Jorma Kaukonen, with his edgy guitar obbligatos, or jazz-schooled Spencer Dryden, who sounds like a different drummer on every track. The volatile Airplane molecule would have destabilized without the bass of Jack Casady, who propels the 'plane on headlong rockers such as "Watch Her Ride," "Wild Tyme" and Kaukonen's "The Last Wall of the Castle," and jams flamenco-style on his brilliant duet with Kaukonen, "Spare Chaynge," the first music that got me excited about improvisation.

The Beatles' "Sgt. Pepper," released half a year earlier, blasted open the door for experimental/concept albums by the Who, the Kinks, the Zombies, the Bee Gees, the Moody Blues and, yeah, the Airplane. In the condensed world of pop, all came to dead ends, even if they moved big units, which "After Bathing at Baxter's" did not. The Beatles had the sense to bury their sound collage "Revolution No. 9" deep in Side 4 of their 1968 "White Album"; "Baxter's" slotted its own at Track 2. That album came off just a little too conflicted, too extreme, even for ears prepped by Jimi Hendrix.

Still, it made some friends. When I happen to mention my love for "Baxter's," I'm surprised at how many fans, especially musicians, get that gleam in their eyes and yell yeah. But genius alone won't pay the bills; you don't draw mobs without optimism, a factor Slick later ladled into the despicable '80s incarnation of Jefferson Starship. As she sang in '67 on "Rejoyce," with a knowing yearn that always gets me, "All you want to do is live, all you want to do is give, but somehow . . . it all . . . falls . . . apart.