The blues became a problem for black avantists of the 1950s and '60s. Once serving to own black pain, the tradition got stolen by George Gershwin and Elvis Presley, and civil-rights firebrands were calling the blues slave shuck. Completely dump the sound, though? For musicians, that would have been like a new set of leg irons. What were they supposed to do?

The answer, often, was to bend and recontextualize the blues.

Duke Ellington added sophisticated arrangements. Ornette Coleman subtracted standard chord changes while retaining the essential cry. Miles Davis cooled, then electrified the blues. Charles Mingus, who in his youth had considered the African part of his multiracial identity irrelevant, embraced the blues to inject revolutionary blood into his epic classical hybrids.

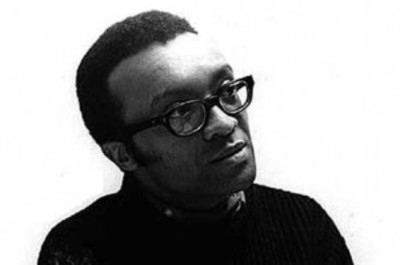

And Cecil Taylor was listening. In his initial recordings of the late '50s and early '60s, Taylor often played blues, employing his piano to reconstruct the form while leaving the rootsier references to saxists such as Archie Shepp, Bill Barron and Steve Lacy, plus his swinging rhythm section of bassist Buell Neidlinger and drummer Denis Charles.

Taylor's swing would soon disappear into extreme abstraction as he virtually eliminated blues from the mid-'60s onward. But Taylor continued to tap it in the form of code, the same way he tapped Stockhausen and Cole Porter. His music came to contain everything, all at once.

Taylor did not limit his art to music. He often incorporated poetry, not only using words abstractly but pronouncing them in ways that brought out percussive and tonal amplifications. Always influenced by his dancer mother, he visualized leaps, steps and pirouettes, and transferred the movements to the keyboard. And color? Just close your eyes and see what comes out of the black.

Richard Meltzer says that when he first saw Taylor perform in San Francisco in 1977, it changed the way he heard music. From then on, it all seemed like a continuation of the universal expression the pianist had condensed and fissionized on his 97-key Bösendorfer.

Like all the greatest artists, Cecil Taylor affected people in ways they did not understand. Many might not have enjoyed what they heard; they may even have felt a kind of pain we associate with the blues. But usually, they kept coming back.