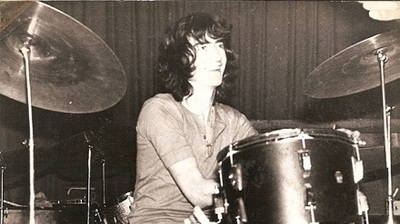

The final exit of Mike Kellie last week dredged up my long-held admiration for U.K. hard-rock drumming around 1970. John Bonham's seismic sock on Led Zeppelin's "Kashmir." Bill Ward's dire slog on Black Sabbath's "Iron Man." Bev Bevan's tar-footed stomp on the Move's "Brontosaurus." Kellie's deadly counterpunching on Spooky Tooth's "Evil Woman."

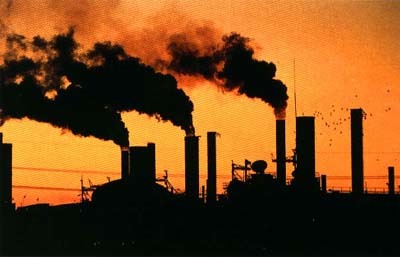

There must be something about England's West Midlands, specifically Birmingham (nearby Redditch in Bonham's case), from which all four drummers hail. Born between 1944 and 1948, they grew limbs amid factory clang & smoke, their steady rhythms beating with a smelter's heart. Above that, they echoed the laborers who manned the machines, enduring the sweatwork with an unhurried pace and more than a couple of pints at day's end.

Artists they were, but not in the mold of the skinsmen who ruled a few years before. The Who's Keith Moon was all fireworks, not exactly a timekeeper. The Jimi Hendrix Experience's Mitch Mitchell followed suit with snapping snare rolls and ear-busting accents. Cream's Ginger Baker expanded the jazz implications with sophisticated layers of driving abstraction. This was rock music before the dominance of heft.

Midwestern American smokestackers such as James Gang, Grand Funk and Crow tweaked Brit ears, and from 1969 onward, heavy was the word. Fortunately, the Birmingham drummers were born with lead feet. And unlike their soul-soaked Yank counterparts, they also dug big-band jazz, which lent their wrists a further level of flexible sensuality.

Consider the drum groove that begins Spooky Tooth's "Waitin' for the Wind" (1969). It was unusual to start a song with 35 seconds of a simple, unaccompanied kick-snare-hat beat like Kellie's, and surprising for a listener to get sucked in so totally by so little. The method works because it breathes, and because the skins sound like flesh.

Bonham adds a rustling ride cymbal to the formula on Led Zeppelin's "Out on the Tiles" (1970). The way his bluff relaxation resists (yet complements) Jimmy Page's nervous guitar riff is just about enough to stop your heart -- sheer genius.

Same groove but slower: the Move's "It Wasn't My Idea To Dance" (1971), reflecting Roy Wood's tale of sexual oppression with a sickly, sticky rhythm; each beat of Bevan's pounding laggery registers halfway between a pant and a sob. Expressions like this led Tony Iommi to replace a collapsed Bill Ward with Bevan on Black Sabbath's 1983 "Born Again" tour.

The booze, the Ludes -- Black Sabbath choked the Midlands beat to the point of passout on "The Writ" (1975). Inspired by a lawsuit with their manager, the song reeks with nauseated boredom; Ward sounds as if he's swinging pine logs instead of drumsticks. For the closest Kellie connection, check the bridge beginning at 3:38.

Industrial central England also has a right to claim drummer Dave Holland, from Rugby (proud purveyor of turbines and cement). Although he didn't show it much in his circa-1970 work with the funky Trapeze, Holland could tap the Midlands grind, as he proved in 1980 with Judas Priest on "Metal Gods," the tune singer Rob Halford illustrated by imitating the locomotive chug of a mechanical giant.

Free's Simon Kirke should fit in here somehow, but he's from a little town on the Wales border, so I dunno where he got his mighty plod. (Oxen?) The relentless foot of Deep Purple's Ian Paice owes something to his youth in the outskirts of Oxford, manufacturer of steel and MGs. Young Jerry Shirley (b. 1952) of Humble Pie was a suburban London lad; he must have inherited his brawny crash by way of his northway countrymen.

Regardless -- here's to the stout-hearted men who trod down the last bloom of flower power. They heard the dark metallic future, and they pointed the way to surviving it.