She sings it "devilution," so maybe Esperanza Spalding knows what spirits possess her. Within a decade, the 31-year-old bassist-singer has boiled through so many alchemical Changes (poetic narrative, Cuban jam, chamber abstraction, etc.) that it felt right to hire morpho-man David Bowie's producer. Even Tony Visconti can't shape Spalding's protean brilliance into a missile of mass impact, though, and anyway, that's not what she wants.

If Spalding lusted for pop stardom, she would not have followed up the big-selling and more direct "Radio Music Society" with "Emily," her knottiest statement. Apparently she desires nothing less than to be herself (selves?) -- the kind of aspiration that satisfies a talented artist's soul and sets her accountant a-weepin'.

From the very start of "Emily," Spalding twists the confrontational knife with the album's most abrasive track, the jittery, dissonant "Good Lava." Expectations, goodbye. The tune's psychedelic jazziness echoes that of Jack Bruce -- not the bluesrocky Bruce of Cream, but the later solo Bruce of impenetrable experimental songwriting. Similarly, Spalding's effortless head voice and breathless phrasing, as on the liltjazzy "Noble Nobles" (nice Bowie "Space Oddity" strum by Matthew Stevens), recalls Joni Mitchell -- not "Free Man in Paris" Mitchell, but the forced jazz hipster of the late '70s. Spalding can do justice to a Laura Nyro R&B moan ("Judas"), too, but shows little interest in composing anything as simply connective as "Stoned Soul Picnic." Pop ain't her. Yet.

Funny thing is, Spalding owns pop chops and pop instincts, but for some reason (misplaced elitism?) keeps sabotaging and camouflaging her hooks. Just when the soaring chorus of "One" portends grand emotion, she undermines the sentiment (and Stevens' charged solo) with rhythmic mindfuck and Slonimskyan harmonic exercises. The leaping, silky balladry of "Ebony and Ivy" is wrecked with robot-voice interpolations that divert attention away from her staggering musical virtues and toward her less sophisticated sociopolitical observations. Yet, again, Spalding knows her devils, displaying the schiz via two versions of the sexy, melodically memorable "Unconditional Love" -- one choked by beatfreak counteraccents, the other allowed to stretch out and breathe its beauty, draped with a long, spacy Stevens solo.

For further evidence that Spalding doesn't despise straight songcraft, please consult "Change Us": Aretha meets Hendrix at Lovers' Leap, just laying it out naked and real. Now, did that hurt?

Spalding has a headful of ideas and wants to use them all. This puts distance between her and the listener, and one is tempted to say she needs an editor. But she's doing damn well without, and if you like self-expression, you're getting it: a portrait of a prodigiously talented musician with an unusual combination of nervous energy, joyful charm and polished cool. You know who else had that? Charlie Parker, and plenty of fools told him to go get regrooved. Call Spalding jazz (and therefore idiosyncratic) if you want; she doesn't care about labels any more than Bird did.

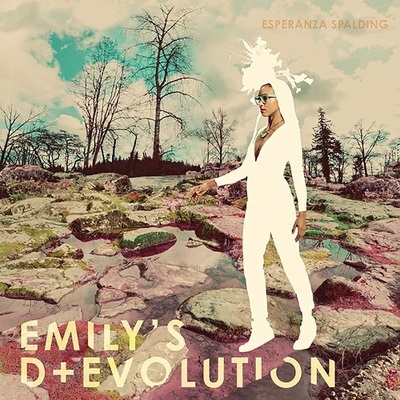

The "Emily" of the title is Spalding's middle name, and a character she invented to reclaim "uncultivated curiosity." (It's also the name of her younger backup singer Emily Elbert, whom I reviewed here.) We cultivate, they say, in order to grow.

* * *

Esperanza Spalding brings an unusual theatrical presentation to the Belasco Theater on Tuesday, March 15.