Many of those who crowded California Plaza's amphitheater were itching for a flash of Kamasi Washington's famous rapper pal Kendrick Lamar. They didn't get that, but they did get some rappin', and they didn't get just jazz, a term widely and often correctly used to denote tediuz soundz for old folks. Washington wants to undermine that perception, and with his new triple album, "The Epic," he does.

Drawing from other decades' contemporary music vibes, Washington conceived tonight's concert as a commemoration -- let's not say a celebration -- of L.A.'s 1965 and 1992 racial uprisings, the theme of Grand Performances' "Los Angeles Aftershocks" series. Since he was 11 in '92, it might seem surprising that he connects more deeply with '65. The tie made more sense when we heard his shout-out to Leimert Park and its World Stage, the cultural boilpoint where Washington stockpiled vital knowledge from the late great drummer and Stage mainstay Billy Higgins.

In 1965, Higgins was well positioned to propagate his smiling, swinging brand of revolution. After busting out with Ornette Coleman in the late '50s, he soon accompanied game changers such as John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, Cecil Taylor and Steve Lacy, and pushed forward to collaborate with every other major jazz figure and define generations of jazz drumming. The same year the fires burned in Los Angeles, Higgins performed on Rollins' "Our Man in Jazz," Dexter Gordon's "Gettin' Around," Eddie Harris' "The In Sound," Hank Mobley's "Dippin'" and Lee Morgan's "Cornbread." Sans Higgins, 1965 saw the recording of avant-garde landmarks such as Coltrane's "Ascension," Coleman's "At the Golden Circle," Albert Ayler's "Bells," Sun Ra's "Heliocentric Worlds" and Archie Shepp's "Fire Music." It was one hell of a year for black expression.

And through Higgins, Coltrane and a raft of other models, Washington has acquired a hell of an affinity for that time. On this night he staged two ensembles, including most of the players on "The Epic," and rolling crescendos of thundering abstraction á la "Ascension" swelled naturally from the more jazz-oriented unit. Sympathetic echoes of the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, founded in the early 1960s by Leimert Park regular Horace Tapscott, were not accidental -- Washington even pointed to superb pianist Brandon Coleman and shouted, "Horace Tapscott!" Straight jazz grooves, too, gained a touch of momentum by omitting the massed strings and vocal choruses of the album.

Both jazz and hip-hop, though, lost traction when the two linked up. Many artists have concocted such fusions -- including Roy Hargrove, Christian McBride and even Miles Davis -- and none has truly clicked. Why? Jazz is improv; hip-hop is recapitulation. Jazz rhythm is flexible; hip-hop uses beat boxes. Jazz is abstraction; hip-hop is description. When jazz goes gangsta, it sounds stiff; when hip-hop honors musical history, it sounds forced. (Higgins, by the way, told me he hated rap.) The musicians shared by Washington and Lamar have sure got the skill and affinity to switch modes, but when they push the two together, the gears grind some. Still, the cover of Cypress Hill's "I Ain't Goin' Out Like That" (the original, recorded in '92, sampled Black Sabbath) kept the truck rolling.

Overall, the program racked up a big musical and political score. Given the headlines of 2015, Washington could not have picked a better time to point a finger at what happens when minorities get stomped and ignored. From 1965 to 1992: 27 years. In the wake of all the broken promises after 1992, L.A. might not have to wait another 27.

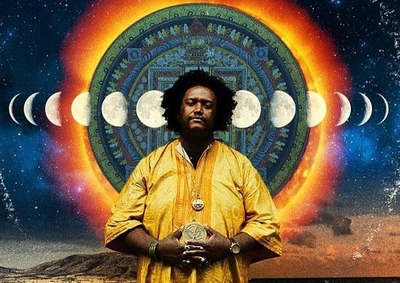

Washington, though, is a man of peace, unity and justice, an attitude that extends to his white robes and desert-prophet hair -- kinda kulty, but I dig it! May he receive 30 wives, a billion devotees and a platinum-plated ashram. Or a lifelong career in music, whichever he prefers.