I moderated an Angel City Jazz Festival/Jazz Journalists Association panel on "New Technologies in Jazz and Jazz Journalism" Friday evening, and it was quite the fun gab. Kneebody's Adam Benjamin, a giant head looming Ozlike via Skype, expanded about teaching jazz to kids without lying to 'em. Flutist Nicole Mitchell had her own angle on that and explored the thrilling weirdness of performing live with bandmates in different cities through the internet. Veteran writer Kirk Silsbee laid down some journo-history and laughed about the assignments he'd lost by shunning the mighty Tweet. "Icons Among Us" producer John W. Comerford tweeted from the very dais, and wizarded up some web connections to his impending archive of jazz performances and interviews. It shouldn't be long before you can listen to the symposium on the Net; I'll let ya know.

The trio of Jim Black, Tim Lefebvre & Chris Speed pumped with life thanks to the many fields Black and Speed have plowed together in the last few years. We goggled at Black's incessant creativity & physicality as he grinningly lurched toward a cymbal only to flick it with the lightest of tings, whilst stomping like a Hessian on that bad ol' kick pedal. We could've focused on him all night, but then we would've missed the discreetly applied plunks, riffs and echo/fuzz FX of tall beast Lefebvre, holding the middle on electric & standup bass. The elfin Speed cut the abstraction with his earthy tenor tone and mournful plaints -- here's a modern musician unafraid to sustain a long note, and he wrung our hearts to the brink of despair.

Friend Ruth said she liked the way John Hollenbeck's Claudia Quintet blended sounds, and dammit, that's the way I'll listen to them from now on. Sure, I appreciated the unusual textures generated by the overlap of Matt Moran's vibraphone, Red Wierenga's accordion and the sax/clarinet of Speed (returning for double duty), but crisp drummer-leader Hollenbeck's busy, scientific compositions proved a distraction. Aside from a shoogity rhythm on "Wayne Phase," the quintet's overcivilized artistry and funereal demeanor conveyed an attitude of Caucasian self-hatred that was unpleasant even if beautiful, and especially if shared.

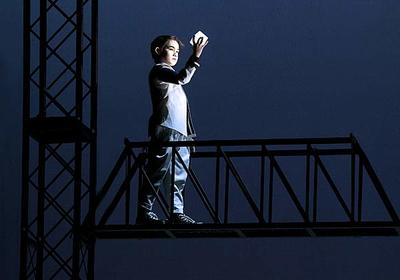

Can't deny that we white folks do despise ourselves, for so many good reasons. Which was one of the main impressions I took away from the spectactular 4-hour production of Philip Glass & Robert Wilson's 1976 "Einstein on the Beach" Sunday. On the one hand, Wilson's staging burned its ingenious contrasts, proportions and movements into our retinas, bolstered by the bold iconography of the Train, the Rocket, the Court, the Prison, the Reactor (alias the Savior). On the other hand, the characters' uniform appearance, robotic motions and disengaged monologues screamed the spiritual death of a hypocritical humanity abandoned to the empty glory and power intended to serve us. Glass' harmonically simple but rhythmically unpredictable arpeggios for violin and keyboards (which stood in for a wide range of templates, from Bach to Kraftwerk) surged and sucked us in, hammering home their mechanical trances too long though rarely boring us. Resonances of flesh surfaced only in choreographer Lucinda Childs' naïvely graceful group dance sequences, and in the unexpected transcendence of Andrew Sterman's Coltrane-like tenor-sax improvisation. "Einstein" held up a mirror that made us like what we see and hate what we feel. When the whole postmodern circus concluded with a saccharine cupcake of romantic love, it felt like the biggest middle finger in the world.

PANEL PHOTO BY DIANA DIAZ.

EINSTEIN PHOTO COURTESY L.A. OPERA.