Different harmonic ideas thrive in different eras. Medieval Gregorian chant started out with no harmonies. The ensuing majors/minors of "classical" music freshened things up and evolved mightily, but they were losing their tang about 100 years ago, when Igor Stravinsky was writing "The Rite of Spring." He was one of the first to drag in a lot of what were then considered dissonances, scraping the earholes of the unprepared.

Gradually, we got more used to hearing kicky extra notes in chords. I didn't know from harmonies when I was a kid, I just knew that the way John, Paul and George sang the last "yeah" on "She Loves You" (a pop-unprecedented E against a G chord, it turned out) gave me a spine freeze. A decade later, when jazz began to rule my ass, I learned that Charlie Parker and Duke Ellington had been digging Stravinsky's harmonies decades before the Beatles, making noises that splashed modern complexity over the industrial ugliness of the 20th century. It all seemed like a political triumph.

So "The Rite of Spring" got to be one of my all-time faves. But until Friday, I had never heard it blasted live. And since young Venezuelan revoltnik Gustavo Dudamel was conducting it with the L.A. Phil . . . It was time.

Let's call the first warm-up, Ravel's 1910 "Pavane pour une infante défunte," a palate cleanser. Static and conventionally beautiful, it felt like pabulum in context. Still, you had to value the exquisite sheen that Dudamel brought to a reduced array of horns and strings.

Then "Symphony," a 20-minute world premiere by longtime LAP associate Steven Stucky, proved to be a lot more than a warm-up. Under Dudamel's baton, Stucky's Stravinskyan harmonies tingled and burned like a champagne bath. The string section bowed with fierce energy. An arsenal of percussion always seemed to be striking a wood block, a vibraphone or a cymbal at the right resonant millisecond. And the thing really flowed, turning up surprise after surprise that made me grin rather than jump, twisting along with a canny intellectual optimism rarely heard in our last century of apocalyptic despair. At the end, scholarly beanpole Stucky came up and got a good hug from thick-haired little athlete Dudamel. When a recording comes out, I'm gittin' it.

Now "The Rite of Spring." Damn, the melodies of Stravinsky's onetime smoke bomb sure have gotten familiar, almost on a Beethoven level. (It was even used for the dinosaur deaths in Disney's 1940 "Fantasia.") Hard to get past that, and harder to penetrate the music's savage heart: The titular rite is a pagan sacrifice in which a chosen maiden dances herself to death -- semi-voluntarily, Igor implies. Maybe Dudamel wasn't quite savage enough, though more savage than most; to do the rite full justice, he'd have to smear the violin strings with ox blood. Balancing the lovely pastoral blooms, though, he did apply major force to the bludgeoning accents, with big drums booming out huge. His masterful rhythm mirrored the relentless onslaught of indifferent nature without a trace of stiffness, and the piece ended with physical shocks maximized through perfect timing. For me, the biggest revelation was hearing the big, brass-laden orchestra press the farthest centimeters of this ultramodern hall with passionate dissonances far nastier than anything I'd felt on recordings, which tend to overemphasize the top lines. We all clapped and clapped, and not just because we thought we were supposed to.

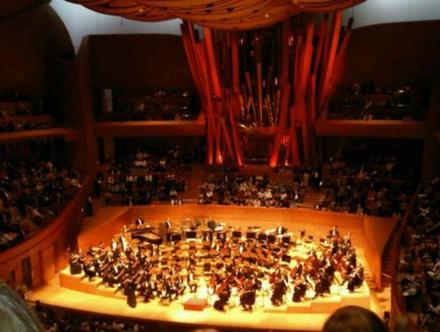

ORCHESTRA PHOTO BY D.D. DOORZ