At REDCAT on Saturday, the panelists on the "Honoring and Breaking With Lineage" symposium strove to make interlocutor Greg Burk (me) look pro, and by all accounts they smoothed over my Grandpappy Amos act pretty well. Before the event, a friend reminded me that I'm not the world's most "moderate" moderator, so I squelched my natural tendencies to booze, curse and beller -- even managed to throttle back the spittle. Historian Steven Isoardi responded with an ecyclopedic contrast of Central Avenue jazz's down-home freshness against New York's nervous urbanity. Despite a killing backache, Jazz Bakery founder Ruth Price charmingly outlined her transition from singer and patron of Shelley's Manne Hole circa 1959 to inventor of a more respectful, artist-friendly venue. Young gun Ambrose Akinmusire (who used his pre-panel moments to warm his trumpet) explained that when he's in timeless bandstand mode, he leaves his influences behind. And cornetist-educator Bobby Bradford blew my mind by suggesting that his former musical partner Ornette Coleman intended the title "When Will the Blues Leave?" not as a challenge to American jazz roots, but as a weary prayer to lose what Robert Johnson called "the worst old feeling that I ever had." Everybody cracked line drives; thanks for the schoolin'.

The trio of Anthony Wilson, Larry Goldings & Jim Keltner then educated us on what happens when you plug a legend of rock rhythm (Keltner has played with Lennon, Harrison, Dylan et omnibus) into a traditional guitar-organ-drums jazz format. The result was novel: Keltner, biker-cool in beard and shades, moved easily through counterrhythms and steady slapdowns that felt like jazz while sounding like rock. Contrary to live jazz practice, Keltner's kit (with both big and li'l kick) was attended by at least nine microphones, a setup that lent unaccustomed oomph to every toe twitch and drew the balance toward center stage, where he sat enthroned. The bignuss didn't overwhelm Hammond squeezer Goldings, who's a spare accompanist anyway and who got to showcase a couple of his own tunes, the blues-grooving "Crawdaddy" and the funky fugue "Pegasus." Wilson stuck to his internal metronome no matter what, milking his Les Paul gold-top for the standard 1950s jazz vocabulary but adding occasional head-tweaking chromaticisms and nastyman chords; he tuned in with special openness on ballads such as Milton Nascimento's "Ponte de Areia," the Jerome Kern classic "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes," Judee Sill's transcendent "The Kiss" and Bob Dylan's audience-pleasing closer, "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue." Not avant, but not entirely retro.

(For a more objective take, check out Matt Duersten's sharp review on the Los Angeles Magazine site, here.)

Sunday swung open to another gorgeous Angel City main event at the John Anson Ford Amphitheater in the Cahuenga Pass. Two old Italian cypresses behind the stage had grown together to become one tree. Dozens of crows fluttered overhead, eyeing the potential carrion below. A black helicopter shot directly over our airspace -- common practice above both the Ford and the Hollywood Bowl across the way; next time I'm bringing my shoulder rocket.

Peter Erskine's New Trio with Vardan Ovsepian & Damian Erskine wafted in nicely with the pre-sunset breeze. I would've been plenty happy to hear the well-traveled drummer P. Erskine alone -- hell, just his CYMBALS alone; the way he stroked and ticked and tingled 'em, you'd think the dude was born with the wrists of an elf. (Talk about the opposite of Keltner: Everything cut through clear with one overhead mike and one on the kick.) From the wide smile that flashed through his white beard beneath his red ball cap, I could tell P.E. was having just as good a time listening to scrape-skulled Vardan Ovsepian, a pianist of nearly equal sensitivity. Despite a somewhat somber European cast, Ovsepian's playing was crisp and light on tunes such as Jerry Goldsmith's "Theme From 'Dr. Kildare'" (the '60s TV series) and his own fizzy "Dreaming Paris," and he slammed into virtuoso self-boxing at the end. Uncle Pete hustled up some railroad snare, and beatnik nephew Damian punched & trilled on six-string electric bass, vaguely suggesting Jaco Pastorius, Peter's old pard in Weather Report. Perfect opener.

The most avant-ageous moments of the night belonged to Mark Dresser's quintet-plus-one. The white-mopped bassist plunged right into his mission to unite every contradiction, wrangling together strums, taps and slides and hurling severe counterpoint at everything from mariachi fiesta to blues groove to total rhythmic fragmentation -- and it hung together! Pianist Denman Maroney added a touch of Halloween to most everything via sliding drones he generated by introducing foreign objects onto the piano wires. The usually outer-than-thou Marty Ehrlich (alto sax and clarinet) and Michael Dessen (trombone) blew hard but not too noisy, referencing post-bop jaggedness and Persian flow. Special guest mentor Bobby Bradford, who played with Dresser 40 years ago in Stanley Crouch's all-star Black Music Infinity with Arthur Blythe, Walter Lowe, David Murray and James Newton, put on his specs to read the charts and brought his warm, human cornet tone to a trailing, wandering groove. Then drummer Michael Sarin swung into "BBJC," a bent-Dixieland tribute to Bradford and B.B.'s old teammate John Carter, with Dessen burbling joyfully on plunger mute before the thing ended with an Ornettish jumpy group unison.

I liked a lot about The Ambrose Akinmusire Quintet. The main grabber was Akinmusire himself -- his soft, open tone; his flow of ideas; his perfect intonation; his variety of trumpet effects (bends, quarter tones, lip flutters, dynamics) on the anguished solo ballad "Regret (No More)." Another plus was the way the band played together -- really balanced and listening. And a third bonus was standup bassist Harish Raghavan, who showed inventive methodology -- alternating pushy figures with standard rhythms for an active, involving groove (and he kept mainly to the low end, which is why they call it bass). I also enjoyed the clean, Joe Henderson-like sax of Walter Smith III, the clashing piano structures of Sam Harris and the controlled-firehose drums of Justin Brown, but mainly for their extraordinary technique and control rather than for their fire or their emotional communication. Where, I asked myself, were the anger and the sex?

Anyway, the anger and the sex were coming right up with Archie Shepp. Now, I have admired Shepp since I was a greenhorn. When I first heard him blow "Hambone" and "The Chased" (both recorded in 1965, the year the avant peaked), I felt that here was a New Thing saxophonist who had it all: the right level of abstraction, an original sound and a ton of passion. He was earthier than Coltrane, more visceral than Ornette, more centered than Ayler, more serious than Rollins. The only time I saw him before Sunday was sometime in the '80s at Catalina's, when he held back quite a bit for the supper-club crowd and he was rumored to have been experiencing lip problems -- though I remember being devastated by this onetime down-and-outer's rendition of "The Good Life."

So I was not prepared for Shepp, looking sharp in his hat and suit despite thin shanks, to demonstrate beyond any doubt that he has everything he had in 1965 and more. His sax sound blurted forth with all the old richness, the mouthpiece deep past his teeth, the lips flapping and the cheeks sucking to make every note drop like a piece of prime raw meat. Mostly on tenor but a bit on soprano, he teased his rhythm further behind the beat than ever. And he never ran out of ideas: When he called Akinmusire out to blow what turned out to be a quite considered solo, Shepp made the younger man wait for about five minutes while he explored every corner of his own extrapolative imagination.

Shepp dedicated "Hope 2" to the unsung pianist Elmo Hope, the Coltraneish jam "Ujaama" (with Akinmusire) to his daughter, and the anti-racist poetic diatribe "Revolution" to his slave-born grandmother. Pieces of "Sweet Georgia Brown," "Nature Boy" and "Twisted" cropped up like prehistoric skulls beneath the plow as pianist Tom McLung comped with casual mastery, bassist Avery Sharpe held the rocking vessel together, and drummer Steve McCraven whomped with random glee. (McCraven also stepped forward to slap legs and face with incredible rhythmic verve and sang the call-and-response street tradition the Hambone like an asylum escapee.)

And Shepp sang. This was no afterthought: He's made his soulful roar a major part of his show, and man, did he sell his perennial brand of Ellingtonian autobiography with "Don't Get Around Much Anymore" and Billy Strayhorn's "My Little Brown Book." For an encore, he even woofed some R&B: "Gonna boogie till the morning comes!" And if there'd been a budget for the stagehands' quadruple overtime, I believe he would have done it.

(Matt also reviewed up a storm and posted superior pix on his own site, here.)

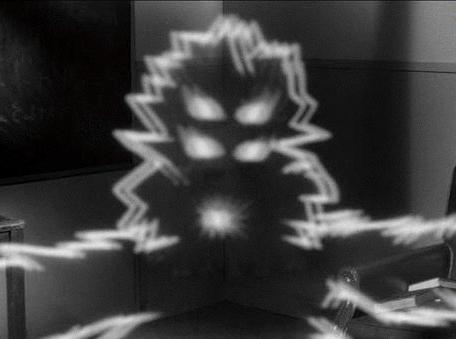

PHOTOS BY DEBI DOORS AND FUZZY BEERQ, EXCEPT FOR THE B&W AT TOP, WHICH IS ECK, FROM A 1960S "OUTER LIMITS" EPISODE. SEE IF YOU CAN SPOT ECK IN THE ARCHIE SHEPP PIC.