A Greek architect-mathematician who became a composer. A flaming conceptualist. A rad commie who got half his face blown off battling WWII Brit occupiers. The character of Iannis Xenakis, who died 10 years ago, makes for a good story, and the exhibits, symposia and performances recently strewn around L.A. in his memory have provided an occasion for deep X consideration and the free consumption of tasty Greek suds. I caught the middle program of three REDCAT nights; the works from 1956 to 1981 expanded my Xenakis horizons and mostly kept me awake.

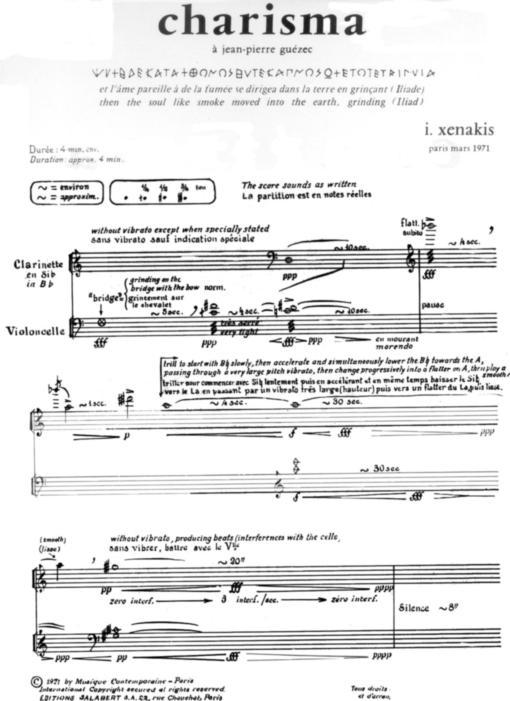

An inexhaustible demiurge, Xenakis balked at the horror of completion, so his music sometimes comes off more as a showcase for his expansions of lexicon than as a holistic statement of form and emotion. That's fine, as demonstrated in the three solo and duo executions of white-shirted, white-haired onetime Xenakis cellist Rohan de Saram: We were knocked out by effects such as microtonal drone harmonies, alternate tunings of the low string and eerie glides. "How do you notate that?" asked my wife. Good question; mine was whether Xenakis would have been surprised by de Saram's interpretations. The cellist's rhythm rocked, but his unearthly sensitivity lacked force; his incredibly detailed shadings of chord and tone didn't penetrate the anger and muscularity the structures implied. De Saram said "Kottos" was based on a myth wherein rebel gods were thrust back into the earth, an event Xenakis represented via multi-overtone grinding that emerged here as nonviolent pumice abrasion. I preferred "Charisma," de Saram's duo with clarinetist Lori Freedman, whose shrieking clusters and intense circular breathing highlighted the drama of a score dedicated to a composer prematurely taken in a car crash.

The raindrop counterpoint plinkings of "Achorripsis," performed by a youth-dominated chamber orchestra under the direction of Mark Menzies, made little impression until the ensemble surged into a bearlike onslaught toward the end. Xenakis' mathematical methods might have bloomed more fully on his chalkboard than in this particular rendition.

The program finished strong with Robert Cucuzza's staging of "Pour la Paix," a piece for narration (libretto by Xenakis' wife, François), movement, lighting, chorus and "electroacoustics" (still called audiotapes in 1981). If paix lacks thematic originality, guerre is a subject Xenakis knew, and this portrayal sweated with humanity and pain. The four mummers/narrators used bright flashlights to probe our flinching eyes and to conjure looming faces and menacing silhouettes on a black curtain. The allusive words stayed subdued: "The gods who did not exist were in agony." The prerecorded electromusic, which sounded like sped-up synth burbles, ran alongside like a deep flood, as it did intermittently throughout the evening. The chorus parts, drawing clear distinctions between men and women, used spare structure and confrontational harmony to achieve fleshly gravity.

We ended up no more opposed to war or complacency than we began, but richer, and disposed to consider our debt to Greece more than the reverse.