In the Old City of Jerusalem, the 12th-century Church of St. Anne stands as the Crusaders’ stone monument to the solidity, simplicity and rigidity of faith. Beneath it lies the chamber where Anne gave birth to the Virgin Mary; the Mother of God was also born in various other locations around town. Severe though its architecture is, the church takes care of its individual congregants -- by its reverberations.

Tourists come here to sing.

Three white teenagers, two girls and a boy, do “Adeste Fidelis” in pure harmony. The walls carry the music upward and spread it out into atoms. The kids smile.

They leave; an African pilgrimage group comes in, the people all wearing yellow baseball caps. They join into a folky spiritual, their voices clinging together like lumps in pudding. The church is cold; they are warm. The sound drips down the walls and settles around their ankles. It’s a good earth vibration.

Not every pile of stones knows something about people and is able to reflect human essences correctly. These stones have had 870 years to learn.

A mile down, at the destination of the narrow, winding alley called the Via Dolorosa, the huge and menacing Church of the Holy Sepulcher is not as proficient at personal service. In its defense, the church has to deal with priests all the time, whole gangs of them from competing Christian denominations -- Greek, Armenian, Roman, Coptic, Syrian and Ethiopian. In sequence, the priests of each sect march around the last five Stations of the Cross; they radiate a certain military attitude, with the Greeks (I think) escorting one main cleric garbed like a Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, except he wears black. When the Roman priests sing the Pater Noster in the chapel reputed to be the site of Calvary, the church’s walls muffle and confuse the voices, making them unmusical. I believe the edifice does this on purpose.

Jerusalem’s Rockefeller Museum is an orderly stone repository with an elegant secular tower. It is empty, maybe because of today’s rain, but it feels as if it’s always empty.

The museum’s prize possessions are coffins and human remains dating from prehistoric times. A wall legend declares that the local chalcolithic (stone & copper) culture vanished suddenly around 3500 BC, around the time when a priestly class emerged. Much of the subsequent art shows an Egyptian influence.

The high-ceilinged rooms are still. Then I start hearing ghostly vocal music with a lot of reverb. How tacky; they’re piping in a Mysterious East soundtrack like in some History Channel show. But the music is growing subtle and layered, and now I’m wondering where I can score a recording of this abstract art; it’s good.

And it hits me: The museum is located in the Arab side of the city. My watch says it’s just after 2:30. What I’m hearing is the Call to Prayer by three or four muezzin, echoing up the hill and through these halls. In any Islamic land, this semi-accidental harmony is the most soul-touching music a tourist is likely to hear.

The 1938 inauguration of the Rockefeller Museum (then called the Palestine Archaeological Museum) was marred when archaeologist J.L. Starkey was murdered by locals on his way to the ceremonies. The motive has been attributed to either robbery or politics.

Jericho, a site inhabited for some 10,000 years, currently lies under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority. Israelis can’t enter without special papers; as with other West Bank areas, the road hits a barricade where very young soldiers, many of them women armed with bulky automatic firearms, make quick checks of vehicles coming and going. Just outside the small, dusty city stands a rusty 40-foot metal sculpture of a key, surmounted with a Palestinian flag and bearing the motto “We will return.”

Deb and I are being driven by our Arab guide, Osama, to see the 8th-century sultan’s palace, the excavations of the world’s oldest fortifications, and the Greek monastery at the traditional site of Jesus’ temptation by Satan. When we’re finished, Sam cuts us loose for a half-hour stroll around the quiet little town square -- scarves; tiny birds crowded in cages; falafel frying; great gatherings of fruit and vegetables, plentiful here because the area is watered by a number of springs.

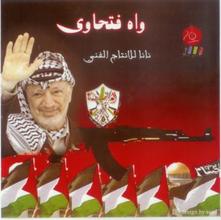

We spot a music store the size of a large closet, with CDs and tapes in racks that stretch up to the ceiling. The proprietor is on the phone; he stays on the phone. When at length he ends his call, he wants to sell us nice music. I say I want music that says “Grrr.” He reluctantly lets us audit a few records that feature aggressive rhythms and intense vocals backed by semitraditional Arabic dance instrumentation. I buy “Gaza Will Not Die” and “The Story of the People.” Deb has explored the stacks and grabs a CD with a picture of Yasser Arafat and a machine gun; she doesn’t care what it sounds like. (Turns out to be Arabic hip-hop.)

The proprietor slowly wraps our purchases. He does not look up; he does not smile. But he takes our shekels. Business is slow.