A small, clean-lined place hidden in Highland Park. Big windows, L.A.-historic photos on the wall, eight tables, four stuffed beige armchairs, students glued to laptops and coffee cups. Two guys positioning standup basses. The drummer is late.

Charles Sharp is a tall, thin California professor of 39 with sandy hair. He wears glasses and chinos, looks surprised to be somewhere as he sets up a baritone, a tenor, an alto and a clarinet. He will face his band while playing, his back to the dozen patrons, half of whom didn’t come for the music but don’t mind it. They don’t know they’re lucky to be there.

Drummer Andrew Lessman, a scruffy kid just out of CalArts, turns out to possess veteran skill and confidence, scattering rhythms actively around the kit with light sticks, providing definition amid the two standups’ busy thrum. The bassists are Jeff Schwartz (Sharp’s age, often choosing to use his bow) and Anthony Shadduck (10 years younger, dark-bearded, pluckier). The two interact well; close your eyes and it’s like one big low instrument.

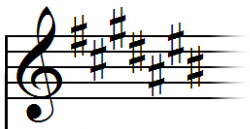

Without even warming up, Sharp launches the first tune by sticking the baritone and the tenor in his mouth simultaneously and whipping off some quick harmony riffs -- like Rahsaan Roland Kirk, but cleaner and more in tune. Impressive, and it’s the last time in the set he’ll execute that technique. It soon becomes clear that Sharp has developed a distinct approach to each instrument. His baritone swings. He’s very gentle with the tenor, sometimes producing soft, pigeonlike pinch tones. His alto sound is thick and dark. He flutters on B-flat clarinet during a slow blues, emphasizing its woody low register. On clarinet and alto, he’s able to smear a note smoothly across a full octave, a trick few beyond the late Johnny Hodges could pull off.

The set’s lone non-original, introduced by Shadduck’s deliberate, Charlie Haden-like elegy, is the romping “Law Years” by Ornette Coleman, whose influence occasionally shows up elsewhere, in Sharp’s tart note choices. Generally, though, Sharp’s solos reflect his own aesthetic -- cogent melodic thinking broken up with spontaneous split tones. His writing is distinctive, too -- snaky, moody lines with a vaguely Arabic-African flavor (shades of Randy Weston), avoiding the frenetic quality of much avant music.

And Sharp is an avantian. So when two women at a table are talking louder than the band, or when the espresso machine hisses out a penetrating slurp, he and the band don’t get rattled. They just consider it part of the music, and play along.