A guitarist who plays metal, and also plays jazz. What web site would be a good place for an interview with Alex Skolnick?

Skolnick was just turning 15 when he joined the Bay Area thrash cornerstone Testament in 1983; he twinned with guitarist Eric Peterson behind singer Chuck Billy on the group's first five albums, from 1987 to 1992. Since then, he has swung his metal mace with a few other groups, including Savatage and Trans-Siberian Orchestra, with which he toured for several years. After studying music at New York's New School, he kicked into jazz mode and formed the Alex Skolnick Trio, knocking out three albums that often feature jazz covers of heavy-metal tunes -- you might not recognize 'em if you didn't know. When a 2005 reunion with Testament proved amicable, Skolnick made the well-received "The Formation of Damnation" with his old mates last year (read my review here), and has been tearing up the road behind it ever since.

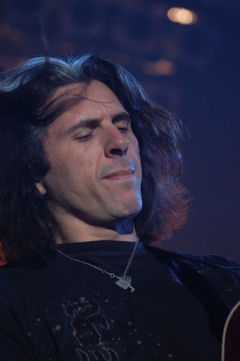

Quite an interesting musician, this guy: total crazed blazing ax-tossing psychedelic maniac in the metal arena, thoughtful coolster when he settles into jazzville.

I talked to Skolnick last October, and have been waiting for him to slide through town again so I'd have an excuse to run this interview, in which he talks about his stage moves, how he almost joined Ozzy's band, and how he's been inspired by Henry Rollins. Really!

Testament plays House of Blues Sunset Strip on Thursday, June 11. The Alex Skolnick Trio plays New York's Fat Baby June 25 and tours Europe in the fall.

* * *

BURK: Seems like you're enjoying playing metal these days.

SKOLNICK: "Y'know, it's fun! It's actually more fun for me, because it's not the only thing I do. So I don't feel like I've got these other creative ideas that can't get out. I have different outlets for different parts of my creativity and my playing. And I really need a balance in order to be happy."

A lot of musicians feel that way, but not many have been able to execute a solution.

"Well, I have some very diverse role models. Pat Metheny is one. You listen to some of his albums with the Pat Metheny Group, and it's music that's very accessible, easy to listen to. I definitely wouldn't call it easy-listening, however! It's very challenging harmonically and melodically, but he somehow makes it very accessible. And he goes from that music to straight-ahead jazz with his trio, and as a sideman, people like Abbey Lincoln and Michael Brecker and so many others. And free jazz with people like Ornette Coleman. And a couple of things I've heard where it's just full-on, like, punk-rock noise. Somebody like Metheny, he's setting the standard.

"And then on a really different level, I look at somebody like Henry Rollins, who comes from punk rock, and he's supposed to be a punk singer. But he happens to be an expert on many kinds of music. He can speak about John Lee Hooker or Thelonious Monk with as much knowledge and perception as any critic in blues or jazz. And he's a writer, he's a spoken-word artist -- he's just got a lot of creative outlets."

You ever meet him?

"I have not met him. I've known about him for a while, but I've only recently been reading his books and watching his DVDs, and really . . . I kind of just knew about his music, which I liked, but I'm recently discovering all his other sides, and really relating to him in a lot of ways."

The "My War" album he did with Black Flag has a lot of heavy-metal influences.

"Yeah. How many guys in punk bands would admit to loving Van Halen? Like, he did this great interview with David Lee Roth, where he professed his love for the original Van Halen. He's also a huge Sabbath fan. When Sabbath reunited about 10 years ago, he documented it -- interviewed the band, went to rehearsals.

"So I look at people that are extremely diverse and knowledgeable, and kind of making their own rules. I look at those guys, and what I'm doing doesn't seem that significant. I hear from people all the time that are shocked at what I'm doing. 'You're doing jazz albums, you're playing with a metal band, you're touring with the Trans-Siberian orchestra, you're writing blogs . . . ?' You know? But I have these role models, and to me, that's how it should be done. You should channel every outlet of your creativity that wants to come out."

When you rejoined Testament, did you have to repractice your rock-star moves?

"I had new ones! I think part of it was, having done the Trans-Siberian Orchestra show for a number of years, I got used to playing arenas, I got used to communicating in front of 14,000 people. When you do that night after night, you get used to it, and if you can communicate to that many people with your playing and your moves, you can definitely do it with the large clubs and theaters that Testament is playing. It was also a matter of finding out which moves work with which song. I never want to do moves that seem contrived. It has to be natural. It has to be an extension of what you're feeling."

When you toss the guitar around, it seems to be part of the thrill of playing metal.

"Playing jazz, you're very relaxed and just focused on the music, and not worrying about stage presence. But playing metal, I think I was able to apply some of that knowledge, and do these stage moves, but be just as relaxed as if I was playing jazz. And it took a little while. I think it came pretty quickly. It's been a few years now, that I've been playing with the guys again in Testament -- and I think for everybody, anytime you do a tour, the first few shows you think into it, and you find yourself again. There's nothing like being in the middle of the tour.

"The same goes for playing jazz. You work out the bugs. Once you've done the first couple shows, you start the next shows with this foundation of really being inside the music and the performance."

It must take a long time as a musician to feel that comfortable, whether it's after two shows or 20.

"That's true. And I'm envious of people that find that at a very young age. I think I'm very blessed and fortunate to be able to do music this long."

And you were playing onstage very young. I saw Van Halen with Wolfie Van Halen playing bass awhile back, and I was going, 'Wow, he's so young, how can he be doing this?' And I hadn't thought -- Alex Skolnick was doing it at the same age.

"I never had the attention that some young players get, of being, like, the whiz kid. Which is fine. In fact, I think that it's probably better. Because I've seen a lot of young players get a lot of attention, especially guitar players, like the next great young guitar player. And then once they're not young anymore, it's not as much of a story, and it's hard for them to develop that early attention into a long-lasting career. Whereas in my case, it turns out, like . . . I think I looked older, for one thing. And a couple of the other guys in Testament, Eric and Lou [Clemente] especially, looked much younger. We used to go to bars, and I wasn't old enough to get in. These guys would get asked for ID -- I wouldn't.

"Probably the reason -- I was just considered a band member, even though the truth was, I was much younger. So people now are surprised that I just turned 40. And when I came back to the band a few years ago, people thought I must be in my mid-40s, and I was actually in my mid-30s."

Eric Peterson mentioned that you brought some jazz elements such as strange time signatures into "The Formation of Damnation."

"An example of that would be the song 'Dangers of the Faithless,' which goes back and forth from 5/4 time to 4/4 time. And yeah, that's something that comes from jazz. And then some of the harmonic elements. The thing about jazz is that you tend to focus on different melodic choices than you would in rock. Most rock is very root-based, based on the main notes, the foundations of chords, the thirds and fifths. In jazz they have the ninths, elevenths, thirteenths."

So you use those in the compositions as well as in the improvisations.

"Yeah, you learn to emphasize those, and sometimes even to develop a solo with those as a framework. And it expands your melodic ideas. I think in some ways, that finds its way into my contributions with Testament. I try to make sure that whatever I bring in is respectful to the music -- I'm not gonna try to change it. There's a thin line between being too different and being constructively experimental. I try different stuff, and we see what works. I think in that song in particular, both the melody in the beginning and the odd time signature are examples of things that I would bring in that come from other styles of music."

Louis Armstrong smoked pot for jazz, and Ozzy smoked pot for metal. Does it help one kind of music more than the other?

"I never really related to the pot thing. I grew up in Berkeley, California, where they think it's the '60s, so . . ."

So you rebelled against that!

"It's funny, because I grew up around people who smoked pot every day after school and listened to the Doors. They'd hang out at these parks which are known for protests so many years ago, but this was during the time when I was growing up, in the early '80s, which was just a completely different time in America. I never related to it.

"I also remember trying it, and thinking I was coming up with some of the greatest music ever, and recording it, and listening to it the next day, and it was godawful! So I quit. I got back into it a little bit when I joined the band, because all the guys were into it. But I decided it was not for me. I was going, 'You're a metal band. What are you doing with this hippie stuff?' I just function better with a clearer head.

"I was drinking good wine. Or scotch. But I wouldn't show up to a rehearsal or a writing session with a bunch of alcohol. The time to drink that is after a hard day's work."

Where do you get your work ethic?

"I think it's just figuring it out for yourself."

It wasn't your parents or anything that instilled that in you?

"Maybe subconsciously. It was definitely never communicated to me directly. But also reading interviews with people I admired, and seeing how they operated. I have no moral objection to getting wasted."

I notice from your bio that you have some connection with Ozzy.

"That was in '95. There was a brief period of time when Zakk Wylde wasn't in the band, and they were trying out guitar players -- including a couple of pretty well-known guys that hadn't worked out for some reason. And I was flown to London. And the first round of the auditions went really well, and Sharon Osbourne booked a show in Nottingham at this club Rock City -- it was an unannounced show. I played the show with Ozzy, and he fell in love with having me in his band. I got all excited, but Sharon didn't do the same. They decided to go with this guitar player Joe Holmes that they had also been considering.

"It was a good experience. I got to do a few rehearsals, I got to hang out with Ozzy, I got to do the show."

I've always wondered what influence Sharon had on the guitar-selection process.

"I don't know. I felt like it was a good performance. I'm sure I would have gotten better after a couple more shows. But everything happens for a reason. If that had worked out, I definitely would have lived, breathed and eaten that music for at least a couple of years. In retrospect, I'm not sure that's what I was meant to do. It was cool that I had already started on this other path, and I was already sitting in with jazz musicians and doing my very first jazz gigs."

What made you decide on a trio as the format for your jazz project?

It sort of happened naturally. I had moved to New York. I was getting my music degree. And the trio is a very common vehicle in jazz, whether it's a piano trio or a guitar trio. And I just wanted to have a trio to play around New York. I wasn't delusional, I knew I wasn't gonna be playing at the Village Vanguard or the Blue Note. But just a lot of local jazz clubs that at that point I knew I was good enough to play in. Once we started playing, we were doing, like, standards. We were doing all the typical songs -- Charlie Parker tunes, John Coltrane, the usual Cole Porter stuff.

"And at one point I thought it would be really humorous to have a Scorpions song. So I brought in the song "No One Like You" -- I had actually heard an arrangement for it in a dream. Sometimes you dream music. I've had a few metal ideas as well, where I've heard something in my sleep and remembered it when I woke up. And this was an example. We tried it, and it was actually really fun to play. It felt like a standard. I could do all my stuff. And it was a tune that I knew nobody else was gonna do. That's where it started, and it was such a hit at our shows that I thought, 'We need more songs like this.' So in a really short time they started coming together -- 'Dream On,' 'Goodbye to Romance,' 'Detroit Rock City.' So we had this thing, and we recorded it. And it totally made sense."

The other players in the band seem a little younger than you.

"Yep. Nathan [Peck], the bass player, just turned 30. Matt [Zebroski]is 29. That helps, because I like having their perspective. They don't come from the rock world, the way I do. They're more in tune with the jazz world, especially the jazz world of guys that age. And they're honest about whether they think something works or doesn't work."

Did you look to any guitarist's tone as a model?

"There were a few guys, some non-household names that I related to. One of them is Paul Bollenback. He's originally a Washington D.C.-based player who moved to New York. He plays burning stuff, shredding that metal fans would like. He played with the organist Joey Defrancesco for many years. His stuff with Defrancesco is just smoking. I never heard jazz shredding like that. His tone is very natural, not a lot of processing. I really like it, because he's warm and very acoustic-based. Pleasant to listen to."

You use more treble than most jazz guitarists this side of Kenny Burrell.

"I also wanted a sound that rock fans could relate to. It's a fine balance. I wasn't initially crazy about the tone of a lot of jazz guitar. A lot of it is very low-endy. A lot of it's very processed with chorus. I never liked that, but at the same time I understand as a player that it's easier to play with that tone."

But you're a big fan of John Scofield, who uses a lot of effects.

"His tone has grown on me, but at first I didn't really like it. I've always loved his lines and his compositions, and now I really like his sound, but initially I wasn't crazy about it. And I didn't want a tone like that for my own playing. People were expecting me to do more of like a fusion thing, and I wanted to get as far away from that as possible. People thought I was gonna do an instrumental metal album, or a Satriani-type album. But I wanted to the opposite from what everybody expected, and Paul was the model for my tone.

"Another guy is Randy Johnson, another great player that more people should know about. He's played a lot with Lou Donaldson. In fact, they're still playing together."

What's going on with the Jim Steinman collaboration in the Dream Engine?

"That's completely on hold. We did a few shows in New York [in 2006]. It was really exciting -- Bonnie Tyler was the special guest. It was Jim Steinman's music, with these great, great singers. And it looked like this was gonna be a regular project. But last I heard, Jim is working on a musical version of 'Bat out of Hell.' When that's done, we'll see what's gonna happen."

It's not like you have all the time in the world, either.

"I know, it kind of worked out. Here it is a couple of years later, and I'm just slammed with everything else."

Whose idea was it to bring you back into Testament?

"I think the guys, Chuck and Eric."

They thought people were interested in seeing the classic lineup?

"I was already a special guest with them. Every few years I would sit in as a special guest, either at a gig or on a recording. I did 'First Strike Still Deadly' [2001], which is the re-recording of the classic songs. And Chuck and Eric would come and see my trio every time we played the Bay Area. We'd hang out and talk about it, and we'd say, 'Sometime we should do a couple gigs.' And I said sure, especially now, this would be really interesting. Because I'm doing the jazz stuff, and to jump back into the metal with Testament would be really cool.

"It finally made sense in 2005, when there was this festival in Europe -- the original Anthrax was back together at that time. And the promoter made a good offer, and said, 'We'd really like to have the original Testament for this show as well. What are the chances we could get it?' And Chuck said, 'We've been talking about doing something for a while, so maybe this could be it.' Some other gigs came through, so we did this 10-show tour of Europe."

So you're getting along with them well these days.

"Oh yeah, great. The whole thing was to jump in, see how it goes. Have a good time, no pressure to do an album, no pressure to do a tour next year. And we had so much fun! It led to a new album and more shows, and here we are."

Just a flashback question here: Why do you think early Bay Area thrash records by Metallica and Slayer were so light on the bass?

"I think initially that music was all about guitars, and that was just part of the sound. It was about having almost like a punk-rock sound, but more polished. I guess at that time having a lot of bass just didn't go with the idea of the sound. But as time has passed and production has gotten better, it's gotten easier to capture the bass. There's been a whole style of recording metal that's developed. You know, there were very few metal producers back in the day. And you'd either have a very garage-band-sounding albums like Venom and Motorhead, or you'd have very polished hard rock like Judas Priest and Iron Maiden. I think for the first few groups that combined those, like Metallica and Megadeth, they went through several different producers.

"In the time since then, there've been all these bands that have followed in their footsteps, and as that happened, there have been different styles of recording and producing the music that have developed. So the bass has sort of found its place in the music."

Thanks, Mr. Skolnick. I look forward to your developments.

"There's a lot more to come!"