Though the tradition of the scapegoat enters the Western mind through Leviticus 16, its origins likely date back much earlier than Judaism. In the time of the Chosen People's desert wanderings, Yahweh was only one of the gods operating on the regional stage. He struggled to establish an identity by assuming the rituals and roles of other deities, such as the child sacrifice to Baal implied in the story of Abraham and Isaac, or his fertility covenant ("I will make of you a great nation") reflecting the function of Asherah.

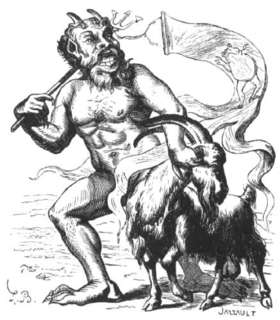

Sometimes it was appropriate for Yahweh to oppose himself against another god, as when the Hebrews established their Day of Atonement. The rite involved two goats, one to be slaughtered in sacrifice, the other to take the people's sins upon itself and be driven out into the remote desert, where the transgressions could be quarantined under the domain of Azazel, the lord of those parts. The living goat was the one that escaped -- the scapegoat.

Our image of a horned Satan derives from the demonization of pagan god symbols, especially the bull of Apis and the crescent moon of Astarte. The horns of the goat fit well into this picture, both because of the desire to subvert Azazel into an anti-Yahweh, and because of the connection between the goat and sin.

When we sin, a scapegoat always stands ready. In the case of our destroyed economy, the scapegoat of the moment is the insurance conglomerate AIG, recently translated by one of our guiltless legislators as Arrogance, Incompetence and Greed.

But another interpretation resonates more deeply and truly: Azazel Is God.