Since the Master Musicians of Jajouka make healing music, they oughta be getting real popular around now. This family-centered Moroccan tribe, which carries on a tradition spanning hundreds if not thousands of years, is often spoken of as endangered, but its art may persist. When literacy, technology and “American Idol” have been forgotten, these spirit-raisers can return to the mountain caves their fathers inhabited just a few generations ago -- no luxuries, no electricity, no problem. Their services will still be in demand.

But can they really heal? Rolling Stone Brian Jones, who recorded them in 1968, thought so. So did William S. Burroughs and Paul Bowles, avatars of the avant literary disestablishment. Ornette Coleman, an honorary tribe member after he included the Pan Pipers on his 1976 album “Dancing in Your Head,” still carries the healing torch. In 2001, when I was at a festival of related Gnawa music in Essaouira, Morocco, I met an older English woman who had fallen sick there many years previous, was cured by the sounds and kept her household there in tribute.

For a hint of the music’s power, consult this new live album; the effects can be physical. The record should’ve commenced with the fourth track, “Double Medahey”: The flutes set up a circular-breathing drone with another flute improvising dry abstraction, and it really scrubs your mind clean before the low drums and percussion kick into a swaying rhythm that commandeers your gonadal gravity.

The stubbornest devils will flee screaming at the buzzing locust attack of massed double-reed ghaitas, which dominate the record with their taunting riffs. (The Pan Pipers inhabit the foothills of the Rif mountains.) The imprecisely tuned oboelike vibrations invade flesh on a cellular level, exploding impurities in the same way that your sonic toothbrush blasts plaque. Any evil brain clutter that remains will surely crumble before the spattering, thudding drums and the communal voices warbling with plaintive aggro.

Any Master Musicians record, of course, acts as only a sampler -- when these magi (only 10 here but many more in Morocco, augmented by the handclaps and chants of the locals) travel to a village, they roll all night, sometimes continuously for days. The most accurate example on “Live” is the 18:34 “Allah Allah Habibi Galouja,” which starts out tentatively with the stringed instruments sounding as if they’re tuning up, warms up with call-and-response vocals, perks the senses with some fiddle scraping, and complicates the ever-intensifying rhythm with counter-plucks of the bass gimbri as the audience is inspired to clap robustly along. (The recording was done in Portugal, so the crowd claps on the correct beat.) This ever-varying journey caused my limbs to relax, my lungs to inflate, and my head to shake back and forth in time. Just a hint of a real North African trance, but impressive: My wife and I were listening in the car coming home from somewhere, and though we’d arrived before the track was half over, we couldn’t tear ourselves out of our seat belts till it finished. I dig the way the musicians often end a selection with a quick-rising short flourish, as if they’ve been shot out of the saddle.

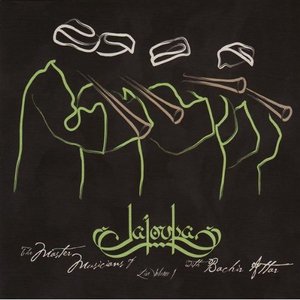

Current Master Musicians leader Bachir Attar has long dedicated himself to bringing this music to the world, and in service to that end makes a couple of warm announcements about longtime Tangier resident Bowles, who died in 1999: “It’s a hero American Paul Bowles, and we never found like him.”

Bowles conducted his own Moroccan field recordings, a touchy process several producers have attempted over the years with the Master Musicians; the advantages of documentation have always outweighed the deficits of partial inauthenticity. I have three other MMJ records, each with its own virtues. On 1992’s “Apocalypse Across the Sky,” Bill Laswell takes an approach worthy of a “4,000-year-old rock ‘n’ roll band” (Burroughs’ phrase) via 13 bite-size nuggets bolstered with a muscular low end. (Laswell also dropped a fun electronicized album with Bachir Attar the same year for CMP.) A trancier attempt is the three 20-minute tracks on the 1995 Womad studio recording “Jajouka Between the Mountains,” whose complex rhythmic overlayings more accurately reflect the way the Master Musicians played when I saw them at Royce Hall around 1996. The new “Live,” without pandering, hews to more straightforward beats.

It’s too bad royalties disputes have laid a cloud over the 1995 CD version of the original “Brian Jones Presents,” because it’s an amazing artifact. Engineer George Chkiantz recorded the ’68 membership of the tribe on site, then Jones, just before his death, edited the tapes and piled on EQ whooshes and studio echo to simulate the drug-addled state he was in during the session. The result, while crazed, doesn’t come off like a goof -- in fact, it’s closer in spirit to the music’s intent than any other representation I’ve heard, including my live experience of the MMJ. This art is not a show, it’s a religious experience, and listening to “Brian Jones Presents” again actually gave me a mild acid flashback. Its booklet notes, which relate the story of Jones eating the liver of a sacrificial goat and believing it was his own, are also worth reading.

After auditing “Live Volume 1,” I was walking through my house and thought I heard it resume. The sound turned out to be blaring from the window of a brand-new red pickup truck, squealing its tires at a stop light in impatient anticipation of takeoff. And it wasn’t the Master Musicians, but a panglobal update. That driver needs a shot of the real thing. The music lives.

The Master Musicians of Jajouka play UCLA’s Royce Hall this Friday, February 6. Tickets are still available from the evil monster Ticketmaster.