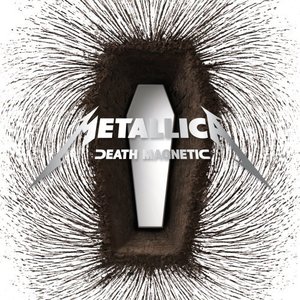

Metallica have invited fans to insert their rigid expectations into the sepulchral vortex that pits the cover of "Death Magnetic," the band's first album in five years. And the four metal revolutionaries have issued the invitation with middle fingers extended, daring haters to come away unsatisfied.

It's astounding how much vituperation the world's most popular metal musicians have attracted over the last 17 years, and when you consider the reasons, you've gotta laugh.1) They failed to keep churning out the kind of speedy humpers that made you bang your head and pity their girlfriends -- i.e., they grew up. 2) They made a lot of money by selling out (writing songs) on their "Black Album." 3) They didn't want their music downloaded for free. 4) While going through personal traumas and attempting a risky new musical direction during the recording of 2003's "St. Anger," they hired a counselor, thus proving themselves sissies. 5) Defaulting on his obligation to die young, singer James Hetfield quit drinking and tried to hold his family together.

Meanwhile, from the "Black Album" through "Load," "Reload," "S&M" and "St. Anger," Metallica stretched out as artists, dismaying diehards with ballads (don't girls like those?), blues (don't black people sing those?), symphonic adaptations (don't old people like those?) and noise exercises (don't art fags like those?). The results, if you happen to enjoy music, have been consistently excellent. And sorry: Despite loud voices proclaiming hate for the records, they sold millions.

By way of sarcastic apology for their success, guitarist-vocalist James Hetfield, drummer Lars Ulrich, guitarist Kirk Hammett and bassist Robert Trujillo (making his Metallica studio debut) have now shown they can still authoritatively execute all the forms their two-three generations of fans have been pining/whining for: the thrash of 1983's "Kill 'Em All," the epic scope of 1986's "Master of Puppets," the damaged croonery of 1991's "Black Album," the roughshod boogie of 1996's "Load." Take it or leave it, the Metallicans seem to say -- and at a rate of nearly half a million copies in its first three days on sale, people are taking it. Because it rocks.

Listening to the thrashy first couple of tracks, "That Was Just Your Life" and "The End of the Line," you may feel as if you're observing Olivier's thousandth performance of "Hamlet" -- of course he's brilliant, but the actual emotions of a troubled young prince no longer pump through his bloodstream. Things quickly get more interesting through the album's middle: the classic Arabic riff and tachycardiac sweep-picked solo of "Broken, Beat & Scarred"; the moody setup and catchy barked chorus of "All Nightmare Long"; the melodic verses and building riffs of the swaggering "Cyanide."

Best is "Unforgiven III" -- since '91, Metallica have created each "Unforgiven" installment as an entirely different song, though all share a gloomy plod and a theme of tortured guilt. The piano-and-strings introduction of "III" bests chamber adapters Apocalyptica at their own game; Hetfield's lyric ("How can I blame you/When it's me I can't forgive") is memorable; and the solo stands as either the most passionate and exciting thing the normally overtechnical Hammett has ever done, or a proud instance of Hetfield himself pouring out his guts through his wah-wah pedal. The instrumental "Suicide & Redemption" shows off a mighty meaty surf-metal guitar sound before traveling through Morricone territory and surging to a huge conclusion. The last track, "My Apocalypse," finds Metallica needlessly revisiting early Dave Mustaine-style thrash; Ulrich batters flabbily as if he can't keep up (or doesn't want to).

Though the songs lurk around the 8-minute mark, they pack enough changes to keep you interested without sounding gratuitous -- another lesson many a young band could learn. The structures don't just switch channels, they develop and cohere.

The mortality-minded "Death Magnetic" deliberately positions Metallica not only within their own history but within the legacy of rock. Their twin-guitar work, originally a tribute to Iron Maiden, has never sounded this much like earlier models -- Thin Lizzy ("All Nightmare Long") and even the Allman Brothers ("The End of the Line"). And try to hear the bright arpeggios of "The Day That Never Comes" without thinking of R.E.M. While dealing a substantial dose of California metal nostalgia, Metallica also hint that listeners might want to acquire a bigger map.

As if to deflect charges of pandering, "Death Magnetic" makes a statement with its sound: hard, unyielding -- metallic, you might say. And the mastering is what Zakk Wylde, in telling me about the first Black Label Society album, "Sonic Brew," described as "stupid-loud" -- if you don't turn this album down before establishing level, you'll risk blowing speakers/eardrums. This has a downside. Stupid-loud mastering, now widespread throughout the industry, is a trend that makes for rapidly diminishing returns: a brutal first impact followed by ear fatigue and a conditioned disinclination for repeat spins. Hard to say whether to lay this decision at the door of the band, recordist Greg Fidelman, an uncredited masterer, or producer Rick Rubin (who, one must say regardless of reports on his policy of benign neglect, continues to secure the kind of ace results he's gotten with Slayer). But listeners are already calling for a remaster that will exploit the music's dynamic range.

Hetfield has unleashed his densest, most sustained roar, and the guitars burn ferociously, and the drums thunder mercilessly (except for a strange tick that makes the kick sound like it's clipping). But issues with the bass guitar remain. Few fans of American thrash will disagree that the job of bassist in a speed-metal band ranks as the most thankless in music; the vacancy in the nether regions of Metallica and Slayer recordings is legendary. However, with Metallica having deliberately lured Robert Trujillo, the bassiest bassist on the planet, away from Ozzy, an adjustment has been made: If the listener boosts the bass, he can experience some breadth and depth, unlike the situation with Metallica's "Ride the Lightning," say, or Slayer's "South of Heaven," where there's almost nothing to boost.

So: What's the vendetta against bass? I asked Maria Ferrero, publicist for early Bay Area thrashers Testament among many others (she was there when the whole thing was hatching), and she replied that Hetfield and Ulrich, being the perennial bosses, wanted to hear the low midranges of the guitar and the lows of the kick drum as clearly as possible, and therefore dipped the faders of the late Cliff Burton and then Jason Newsted. The struggle has raged since the first Metallica album, "Kill 'Em All."

"I think Cliff fought hard within himself to write his bass solo '(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth,' wrote Ferrero. "And it makes sense that he titled that track the way he did -- I'm sure it was like pulling teeth for those cats to let him write a song. Little did they predict that that solo would stand out so far in setting Metallica apart from all of the other bands musically." Despite the album's low budget, Burton was actually dealt pretty good cards on "Kill 'Em All," which roars out of speakers large or small like a bullet train full of explosives.

The real bass hamstringing began with Metallica's breakthrough second album, "Ride the Lightning," bringing up another possible culprit: the producer. The band, finishing a tour, landed in Ulrich's home country of Denmark and decided to record locally with Flemming Rasmussen, who would also produce the next two, "Master of Puppets" and ". . . and Justice for All." With their toilet-tank vocal echoes and baked-potato kick drums, these were surely three of the crappiest-sounding (though compositionally great) records ever to sell a lot of copies. Maybe Flemming just couldn't get a good bass sound, or Metallica decided not to mess with a successful formula.

But let's throw out one other option: the boom-box factor. If you play, say, the LP of "Master of Puppets" through a decent system, every measure screams sonic amateurism. If you blare the cassette on a cheap boom box, on the other hand, the squashed sound rocks -- the little speakers can't reproduce proper bass anyway. Consider the fact that underground trading of demos and live tapes played a major part in breaking American metal. And consider the fact that Metallica, a bunch of kids squatting in dives and traveling in vans, probably trained their '80s ears on the lowest of lo-fi. Most studios have two or three sizes of speakers on which to mix, and five bucks says Metallica routinely mixed on 5-inch cubes.

You know who made Metallica sound great (yet still virtually bassless)? Bob Rock, who had pulled off a masterpiece in 1989 with Motley Crue's "Dr. Feelgood" and followed up with a string of Metallica hits. But he also made Metallica commercial -- sales of the "Black Album" dwarfed anything previous. So that was a bad thing, right? But Metallica have made a career of turning bad on its head.

"Death Magnetic" proves they ain't dead yet. Not even close.