Almost the same band Ornette brought three years ago. Same hall, same time of year. Much of the same material. Entirely different vibe. He's an artist, though, who makes every listener hear different music.

In Randy Weston's new autobiography, the piano master wrote about the period when he was discovering African traditional music: "It was a natural process of listening . . . but not necessarily listening with your ears; it's almost like listening with your spirit."

By instinct, that's the way I listen to Ornette. With most other musicians, it's natural to focus on specifics and the way the group interacts, but that's hard to do with Ornette, because his ensemble sound can't be penetrated -- which is surely part of his intention. He trains his musicians (here drummer Denardo Coleman, upright bassist Tony Falanga and electric bassist Al MacDowell) to maintain an unsettling tension among rhythm, melody and harmony in which the parts are comprehensible individually but not collectively; the music hangs together because his conceptual system -- harmolodics or sound grammar or Colemania -- creates its own kind of balance.

If the rule is followed. For the first time in my experience, there were a few moments when I thought somebody made a mistake. Oh, within all this logic-erasing babble, it's possible to make a mistake? Yes. Those errant instances reminded me of when Jesus' disciples asked him if he was the Messiah; he didn't respond directly, of course, but his attitude was, "You've been following me around all this time, and you're still asking the wrong questions."

Because musicians are trained to make music -- which is not the same thing as harmolodics -- they can't be completely retrained. When Falanga, for instance, was bowing the seesaws of the Bach prelude that's been a part of Ornette's set for some 15 years, the bassist was really getting into the rhythm and sonority of the thing, and it was absolutely gorgeous, but it stayed on that level. So where Ornette would normally play complementary lines in his own challenging manner, this time he wheedled way up into the technical wilderness of his alto to bend into some microtonal notes that were just deliberately wrong. The point: We're not here to listen to Bach; we're here to help you hear differently.

Similarly, Ornette's sax and MacDowell's five-string bass (plucked on the high strings where it sounds like a guitar) were hitting one of their unison passages, which always break down more or less gradually into improvisation, because Ornette isn't interested in lockstep, he's interested in relations. MacDowell hit a note or two that clashed like a dropped tea tray, and Ornette's eyes flicked ever so slightly toward Al, like, "Oh, you played something you thought would sound good. But it wasn't in the scale I wrote, was it?"

This general scenario repeated several times -- the band pouring out the most accessible music I've heard from an Ornette ensemble, including half of 2006's "Sound Grammar"; Ornette subverting them. The subversion could run backward, too: Once, everybody was in the middle of a furious harmolodic groove, and Ornette just knocked out an evenly spaced do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-do, like he was 8 instead of 80. It's that kind of stuff that gets him called both a genius and a fake.

One of the crowd pleasers (a revamp of "Sleep Talking"?) was a beautifully strange number that combined a bunch of unlikely stuff: a shuffly military rhythm underlaid with a sort of disco feel, and droning strings that reminded me of Cream's "As You Said." My wife flashed on the feet of the camel dragging across the sand as it humped me back from the Tomb of the Apis Bulls at Saqqara, which I thought was a great observation.

Not so great was singer Mari Okubo, wearing a kimono AND tight jeans, who came on for one number to wail some opera-toned improvisations with the dudes. Ornette loves to toss a knuckleball, and if the audience swings and misses, all the better. She made my ears hurt, so mission accomplished.

The last 20 minutes featured special guest bassist Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. So what if he was there to pump up last-minute sales; he smoked. Classed up in natty gray Brooks Brothers, his nappy dome dyed turquoise to match Ornette's outlandish plaid suit, Flea headbanged into the revvers (hinting at Ornette's rarely acknowledged influence on punk) and punched out the riffs as if he'd been Colemanizing all his life, which this fine musician probably has been. Fit right in, even on the quietest, most sensitive version of the rollicking "Dancing in Your Head" and the saddest, most subtly shaded version of "Lonely Woman" I've ever heard.

Despite constant drive and variety of coloration, Denardo virtually disappeared into the music, which is about the greatest achievement an Ornette band member can hope for -- 40-some years in Dad's groups well spent. Falanga's arco and pizzicato work was massive and flawless. And MacDowell locked into whatever octave was required at any moment, showing technique to burn, such as blinding right-hand-fingered arpeggios reminiscent of metal sweep picking; with him on hand, no guitar, keyboard or trumpet was needed. As if acknowledging that, Ornette picked up his trumpet on only one song and left his violin untouched on its stand.

One thing Ornette couldn't keep his mitts off: the blues ("Turnaround," "Blues Connotation"), which cropped up often in tone, in structure and in spirit. He has always maintained a special relationship with the form -- vehicle of emotion, reminder of slavery, root of communication, tyrant of tradition. The blues will not leave, and it's another contradiction he's glad to embrace.

Ornette played well, but he looked weary. When he stood with the others at the end, acknowledging the standing ovation, his eyes were turned in our direction. But he was looking inside.

Read my 2007 live review of Ornette Coleman here.

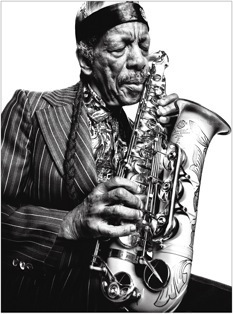

PHOTO BY PLATON.