People walk around in dashikis. The pre-film blurbs feature ads for Ethiopian Airlines. Vendors in the lobby sell MLK DVDs. The yearly Pan African Film Festival at Culver Plaza Cinemas does pretty well, because it serves the underserved.

I'm there to check out a couple of films related to jazz musician Charles Lloyd and his artist-filmmaker wife, Dorothy Darr. On Monday, there's "The Monk and the Mermaid: Charles Lloyd's Song," a documentary by Giuseppi Del Vecchi and Fara C. The camera follows Lloyd around on a European tour when his band jams at a medieval church, or when he praises Billy Higgins and Ornette Coleman (a rare but true tribute to Coleman's technical mastery, and Coleman returns the favor), or when he hilariously wears down a saxophone-company rep. Relaxed pace, pretty scenery, plenty of live music.

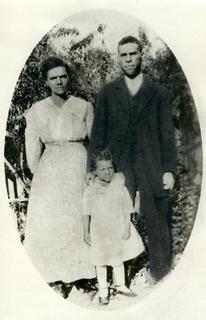

But the emotional peak hits on Sunday, when Darr's documentary "Ben Ingram vs. the State of Mississippi" screens. Ingram, Charles Lloyd's grandfather, was quite a rarity in the early 1900s -- a black man who owned 1,600 acres of Mississippi farmland. Through interviews and archival images of slave lists and Jim Crow signage, Darr sets up the climate that made Ingram's success so improbable, as Lloyd's aching saxophone etches the soundtrack. Then Darr brings down the hammer with the crossroads moment in 1918 when Ingram kills his white neighbor in a boundary dispute.

Self-defense? Extenuating circumstances? It would hardly matter in that time and place, but Ingram can afford lawyers who give him a fighting chance. Sitting in the theater, I can feel the audience's tension as the trial unfolds, and feel the release of that tension when the verdict is declared. In this community, 91 years after the event, there's no question about who's the protagonist.

Ben Ingram was natural and adoptive father to more than 20 children. His story means a lot to his descendants, a score of whom (including his only surviving direct offspring, Alfreda Ingram Moore) gather at the end of the screening to introduce themselves. Looking from face to face, old and young, I think about what a family means. This is the legacy of determination.

Present both days is a wheelchair-bound Buddy Collette, who was born a year after the Ingram trial. As everyone in Los Angeles jazz knows, Collette educated and mentored many an L.A. musician, including Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Frank Morgan and James Newton. On Monday, Charles Lloyd runs down the litany and tells the story of how Collette launched Lloyd's career by recommending him as the replacement for Dolphy in Chico Hamilton's influential art-jazz ensemble. Then Lloyd goes out to where Collette is sitting, greets him, lays a hand on his shoulder, and they both smile. That's family, too.